There has been much discussion, in the latter part of the last century, of our ‘denial of death’. But it would seem to me that the problem is deeper and more difficult. If it is true that Christ shows us what it is to be God in the way that he dies as a human being, then, quite simply, if we no longer ‘see’ death, we no longer see the face of God.

John Behr, “The Christian Art of Dying” in Sobornost, 35:1-2, 2013. 137.

The last issue of Sobornost contains a compelling essay by Father John Behr on the importance of taking back the Christian art of dying. Our culture’s denial of death is something that has been widely commented on, and something that I have become more aware of in recent years. This is not only related to becoming Orthodox (or, perhaps more broadly, engaging more seriously with the Christian tradition), but it does have something to do with it. There is nothing like going to a family funeral when you really need to grieve and pray for the departed, and realising that something crucial is desperately missing. And, linked to this, I have also become aware of the contrast between how aging is viewed in the Christian tradition and how it is viewed by our contemporary western society – as well as the related and potentially huge question of cultural (and religious) shifts in how the body is viewed. So it was against this backdrop that I thought this essay well worth noting and sharing with others.

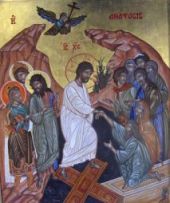

However, this article takes these generally acknowledged issues a step further, for in it Father Behr argues that the fact that contemporary western culture no longer lives with death and dying as an ever-present reality undermines our ability to see something that is at the heart of our Christian faith, for it is in death that Christ shows us what it is to be God. Indeed, “the way that he dies as a human being sums up the theological heart of the creeds and definitions of the early Councils.” (137)

Facing death is an unavoidable human reality, but it is an even more crucial task for Christians. And it is in fact, Father Behr argues, the coming of Christ that has made our facing of death so crucial. Prior to the coming of Christ, death was simply a natural reality, but with Christ’s victory over death, death itself has been revealed as “the last enemy.” (1 Cor. 15:26) For, in the light of Christ, we see that people die not simply from biological necessity, but as a result of having turned away from the Source of life. And this is not simply a once-off occurrence that happened with Adam, but is a constant temptation for us – the temptation to live our lives on our own terms and turned in on ourselves.

It is precisely in death that Christ has shown Himself to be God and in His conquering of death, He has, in the words of Saint Maximus the Confessor, “changed the use of death.”

Through his Passion, destroying death by death, Christ has enable us to use our death, the fact of our mortality, actively. Rather than being passive and frustrated victims of the givenness of our mortality, complaining that it is not fair, or doing all we can to secure ourselves, we now have a path open to us, through a voluntary death in baptism, to enter into the body and life of Christ. Whereas we were thrown into the mortal existence, without any choice on our part, we can now, freely, use our mortality, to be born into life, by dying with Christ in baptism, taking up our cross, and no longer living for ourselves, but for Christ and our neighbours. In doing this, our new existence is grounded in the free, self-sacrificial love that Christ has shown to be the life and very being of God himself, for as we have seen Christ has shown us what it means to be God in the way he dies as a human being. (141)

Christian life is about learning to die so that we may be born to new life – and it is our physical death that will reveal the extent to which we have done this, for it will reveal where our hearts truly lie.

One way or another, each and every one of us will die, we will become clay. The only real question is whether, through this life, we have learnt to become soft and pliable clay in the hands of God, breaking down our hearts of stone so that we may receive a heart of flesh, merciful and loving. Or whether, instead, we will have hardened ourselves, so that we are nothing but brittle and dried out clay that is good for nothing. (143)

Father Behr uses two examples of martyrdom – of Saint Ignatius of Antioch and Saint Blandina – to illustrate this understanding of death as revealing the deepest reality of being born into the new life of Christ. Such accounts have nourished the Church throughout the ages; they have changed our perception of “the use of death.” However, as the essay concludes:

If it is true, as I suggested earlier, that Christ shows us what it is to be God in the way that he dies as a human being, then, if we don’t see death (as I claimed that modern society doesn’t), then we will not see the face of God either. If we don’t know that life comes through death, then our horizons will become totally imminent, our life will be for ourselves, for our body, for our pleasure (even if we think we are being ‘religious’, growing in our ‘spiritual life’). And so, I would argue, we need to regain the martyric reality of what it means to bear Christian witness. Our task today is not just to proclaim our faith in an increasingly secular world; it is, rather, to take back death, by allowing death to be ‘seen’, by honouring those dying with the full liturgy of death, and by ourselves bearing witness to a life that comes through death, a life that can no longer be touched by death, a life that comes by taking up the cross. (147)