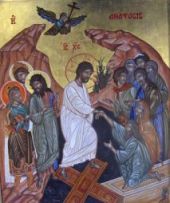

Every year at this time (when we start using the Liturgy of Saint Basil during Great Lent), I am reminded that the Anaphora of Saint Basil is one of the best statement of the Christian faith that I can think of. I saved this as a draft post two years ago and never got to posting it. But I was reminded of it again this morning and thought it worth posting, for I can think of few better expressions of what we believe.

Truly You are holy and most holy, and there are no bounds to the majesty of Your holiness. You are holy in all Your works, for with righteousness and true judgment You have ordered all things for us. For having made man by taking dust from the earth, and having honored him with Your own image, O God, You placed him in a garden of delight, promising him eternal life and the enjoyment of everlasting blessings in the observance of Your commandments. But when he disobeyed You, the true God who had created him, and was led astray by the deception of the serpent becoming subject to death through his own transgressions, You, O God, in Your righteous judgment, expelled him from paradise into this world, returning him to the earth from which he was taken, yet providing for him the salvation of regeneration in Your Christ. For You did not forever reject Your creature whom You made, O Good One, nor did You forget the work of Your hands, but because of Your tender compassion, You visited him in various ways: You sent forth prophets; You performed mighty works by Your saints who in every generation have pleased You. You spoke to us by the mouth of Your servants the prophets, announcing to us the salvation which was to come; You gave us the law to help us; You appointed angels as guardians. And when the fullness of time had come, You spoke to us through Your Son Himself, through whom You created the ages. He, being the splendor of Your glory and the image of Your being, upholding all things by the word of His power, thought it not robbery to be equal with You, God and Father. But, being God before all ages, He appeared on earth and lived with humankind. Becoming incarnate from a holy Virgin, He emptied Himself, taking the form of a servant, conforming to the body of our lowliness, that He might change us in the likeness of the image of His glory. For, since through man sin came into the world and through sin death, it pleased Your only begotten Son, who is in Your bosom, God and Father, born of a woman, the holy Theotokos and ever virgin Mary; born under the law, to condemn sin in His flesh, so that those who died in Adam may be brought to life in Him, Your Christ. He lived in this world, and gave us precepts of salvation. Releasing us from the delusions of idolatry, He guided us to the sure knowledge of You, the true God and Father. He acquired us for Himself, as His chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation. Having cleansed us by water and sanctified us with the Holy Spirit, He gave Himself as ransom to death in which we were held captive, sold under sin. Descending into Hades through the cross, that He might fill all things with Himself, He loosed the bonds of death. He rose on the third day, having opened a path for all flesh to the resurrection from the dead, since it was not possible that the Author of life would be dominated by corruption. So He became the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep, the first born of the dead, that He might be Himself the first in all things. Ascending into heaven, He sat at the right hand of Your majesty on high and He will come to render to each according to His works.