I haven’t abandoned this series, and will hopefully conclude the summary of this article in the following post. I do intend to engage with it more as I am noticing all sorts of resonances. Once I’ve finished this article, I will return to the Florovsky blogging, and possibly return to the rest of this book at a later stage…

Having noted some Orthodox objections to the term “spirituality,” Father Alexander Golubov’s essay on “Spirituality in an Orthodox Perspective”* proceeds to consider western discussions of the term that emerged in the 1960s. He notes the work of Walter Principe and Ewert Cousins, before focusing on the contribution of Sandra Schneiders, which, he argues,

comes closest to Orthodox understanding – at least on the basis of ‘practical’ or ‘applied’ theology – and is useful to us precisely as a sounding board, as it were, for testing aspects of Christian spirituality understood specifically from the Orthodox perspective. (Kindle Location 190)

Schneiders summarizes Christian spirituality as:

personal participation in the mystery of Christ begun in faith, sealed by baptism into the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, nourished by the sharing of the Lord’s Supper [i.e., Eucharist], which the community celebrated regularly in memory of Him who was truly present wherever his followers gathered, and was expressed by a simple life of universal love that bore witness to life in the Spirit and attracted others to the faith. (201)

While it would appear that all the essentials are in place in this understanding, Father Golubov raises “a third major issue in a focused study of spirituality,” namely, that of “the theological context of the discussion, as well as the dangers of facile formulaic definitions taken out of such context.” (201) Spirituality is both formed and informed by theology, which raises the question of the theological meaning of Schneiders’ description. While she gives adequate explanations elsewhere, “in contexts wherein definitions of spirituality, such as the one given above, stand on their own merit, absent a larger framework of discussion, inevitable confusion arises about implicit theological assumptions standing behind such definitions.” (211)

This leads Golubov to argue that “The stark realization, ultimately, is that an externally descriptive approach to Christian spirituality is, at best, meaningless, absent the dimensions of theological definition and evaluation, appropriation and understanding of inner goals and purposes.” (211) Such a definition provides no clear answers to the question of Jesus Christ’s identity, nor does it clarify what “participation in the mystery of Christ” involves. Moreover, such a descriptive approach also lacks an understanding of human nature and the need for a transformational inner struggle.

Is spiritual metamorphosis, or transfiguration, a noteworthy component of Christian spirituality? Or is it that “a simple life of universal love” is somehow (how – magically?) to be attained without need for any internal striving or struggle (askesis) implicit in Christian living, without the necessity of self-denial and crucifixion of the self, as implicit in the injunction “If anyone desires to come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow Me” (Matthew 16:23-25; Mark 8:34-38; Luke 9:23-26)? And is there, in fact, in “coming after,” or “following” Christ, a “way” to be travelled, a “spiritual journey” to be undertaken? Is there any movement, development, growth, direction on the way, or a goal that is to be achieved at the end of the journey? (230)

Finally, there is the question of the role of theology. Father Golubov argues that:

It is, in fact, theology, as intentionally engaged in the process of ongoing theological reflection, that directly imparts both meaning and direction to authentic spirituality, not only in the active categories of speaking or informing, but also in passive terms, as hearing and appropriating, or even in seeking deeper theological understanding.

From this perspective, then, beyond exhibiting the inherent weakness of a purely “descriptive” approach to spirituality, there is implicit in stand-alone definitions of Christian spirituality a certain theological naïveté that speaks, perhaps, to a larger failure of theological understanding; it is here, in fact, that we meet up, once again, with the difficult issues of Christian living that have been identified and raised by Evdokimov and Florovsky. (241)

To be continued…

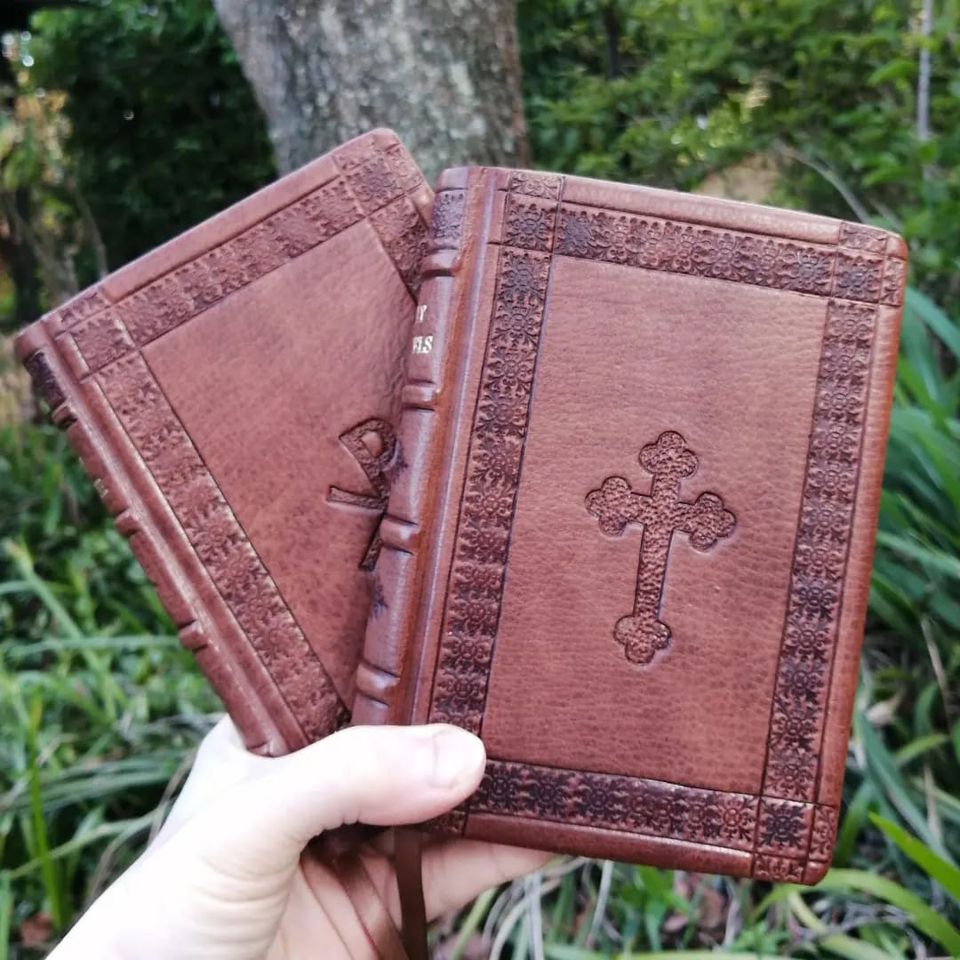

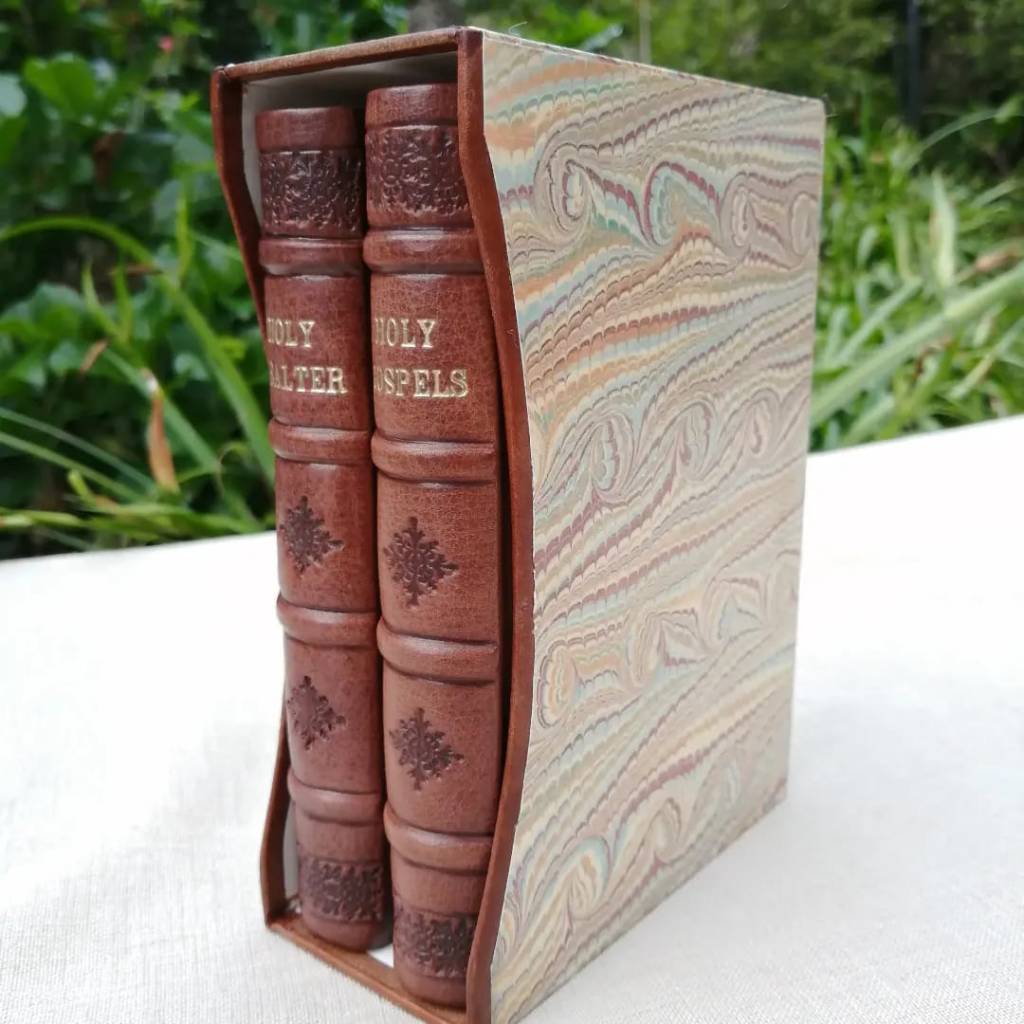

* This forms the foreword to Father Dumitru Staniloae’s Orthodox Spirituality . My previous posts on it can be found here and here.

. My previous posts on it can be found here and here.